I have clients and students who say, “My ancestors were awful people. What do I do?” First of all, it isn’t just you. We all have ancestors who were awful people. Some in different ways, but that is when we do the work of looking at the legacy of awfulness in your family line. If you don’t know your family line or family stories, that is something else to look at. WHY? The legacy in your family is that they do not speak the stories. Maybe they even repeat patterns over and over because nothing is ever learned or grown from. How I work with my great-grandmother, who was lovely to some of her children, and awful to one, I say, “Thank you for letting me be able to see this and break the pattern of the bad mother. Thank you for allowing me to break the awfulness.” (Instead of awfulness, you can replace that with breaker of our family trauma, pain, abuse, addiction, victimhood, etc.) When we reframe our ancestors —putting them in their historical, trauma, and family context —we can find wisdom, even if it is learning from their sins. Sometimes the deep grief of lives not lived, or their actions, can move through us. We can cry for our family lineage. We can cry for their victims, for ourselves, if we were the victim or them as a victim and victimizer.** This ancestral work is about healing and releasing. We get to be the conduit for compassion, love, and grief if we feel the ancestral lineage hasn’t been compassionate or grieved enough. We get to acknowledge the awfulness of our ancestors, too.

But we transform grief into gratitude through this process. Not for having lost, but for them having lived at all. They brought you here, after all, they created people who created people who created you.

Our Ancestors —the good, the bad, and the ugly —have lessons for us because they were human. This is the medicina they bring forth—their humanness. And not that anyone wants my opinion on this, but this is the beauty and awe of the stories of Buddha and Jesus—their humanness existed, their flaws, their character defects and defaults, but still they sought to heal themselves, then others. They found a path of spirituality that helped them and passed it on. This is also the lessons of our ancestors—that they were human and had a story, which is now part of your DNA. (Epigenetics is a cool rabbit hole to go down)

+ + + + +

Beyond just dialogue with my ancestors, I also think about what it means to be a good ancestor.

How do we become an ancestor vs. just another people on the family tree who died?

Writer Layla Saad, whose podcast How to Become a Good Ancestor, prioritizes this concept, as is evidenced by her podcast title. Basically, she says we need to live and work in a way that intentionally creates a more just and liberated world for future generations. That’s the idea. We live in a way that thinks about the next generations, the earth, the future. We each have a role in the ongoing story of humanity. We focus more on making a positive impact, rather than on our personal achievement. And that doesn’t happen magically, it happens by us engaging in our own spiritual, mental, emotional and physical work, such as self-reflection and understanding one's own role in family systems. Being a good ancestor requires us to break patterns of suffering, not just in our personal lives, but the karmic and ancestral patterns we all fall into that keep our children in suffering and then suffering of our community, which means dismantling things like racism, sexism, ableism…other isms (In recovery, we say -ISM stand for I-Self-Me.) We take intentional action and live from a place of hope, rather than just hoping for the best.

+ + + + +

I create an altar for Día de los Muertos* in mid-October, when I begin to feel the ancestors pushing against me. I call them in. Ask for their help. It is not simply because I come from a culture that celebrates this holiday (though I do), but because I am a bereaved mother. And this American happy-happy culture does a lousy job of honoring the dead and grief.

Day of the Dead is one of those holidays that has grown more and more mainstream with non-Catholic, non-Latino people creating altars, painting their faces, hanging up decorated sugar skulls, and dancing into the night. That isn't happening because others want to become or appropriate another culture, but because we are all hungry to honor our dead. We want to celebrate our ancestors. We want to walk with death, rather than hide our grief and whisper to our dead in the still of the night. It is only in recent history that the dead were hidden away from us, or that we were protected from the dying, the dead, and grief. All cultures from Europe to Asia to Africa to the Americas honored the dead.

So Day of the Dead, I create a space for my ancestors and my predeceased ancestral daughter, hang a painting of her and me that I painted in the early days after her death, and another of my ancestors, the ones that whisper to me in my sessions. I put calaveras and bright colors all around the altar as well as food, water, flowers and candles. In my mother's native Panama, my family walks to the cemetery to have a meal with the dead. They decorate the graves and commune as a family.

Those weeks with my Día de los Muertos altar are not simply a time to grieve, but a time to celebrate life. When we honor our ancestors, we acknowledge the wisdom they have given to us in life and now in death.

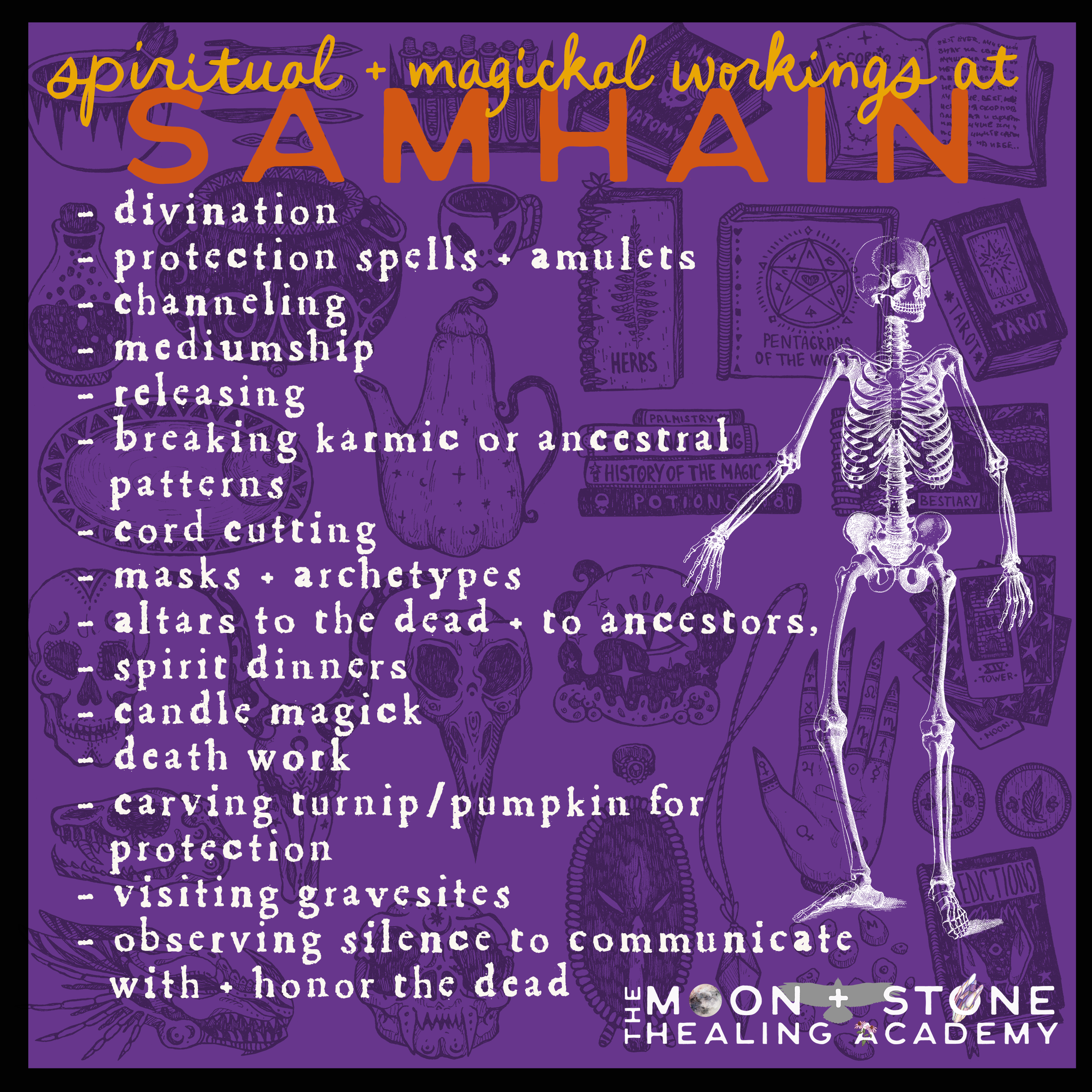

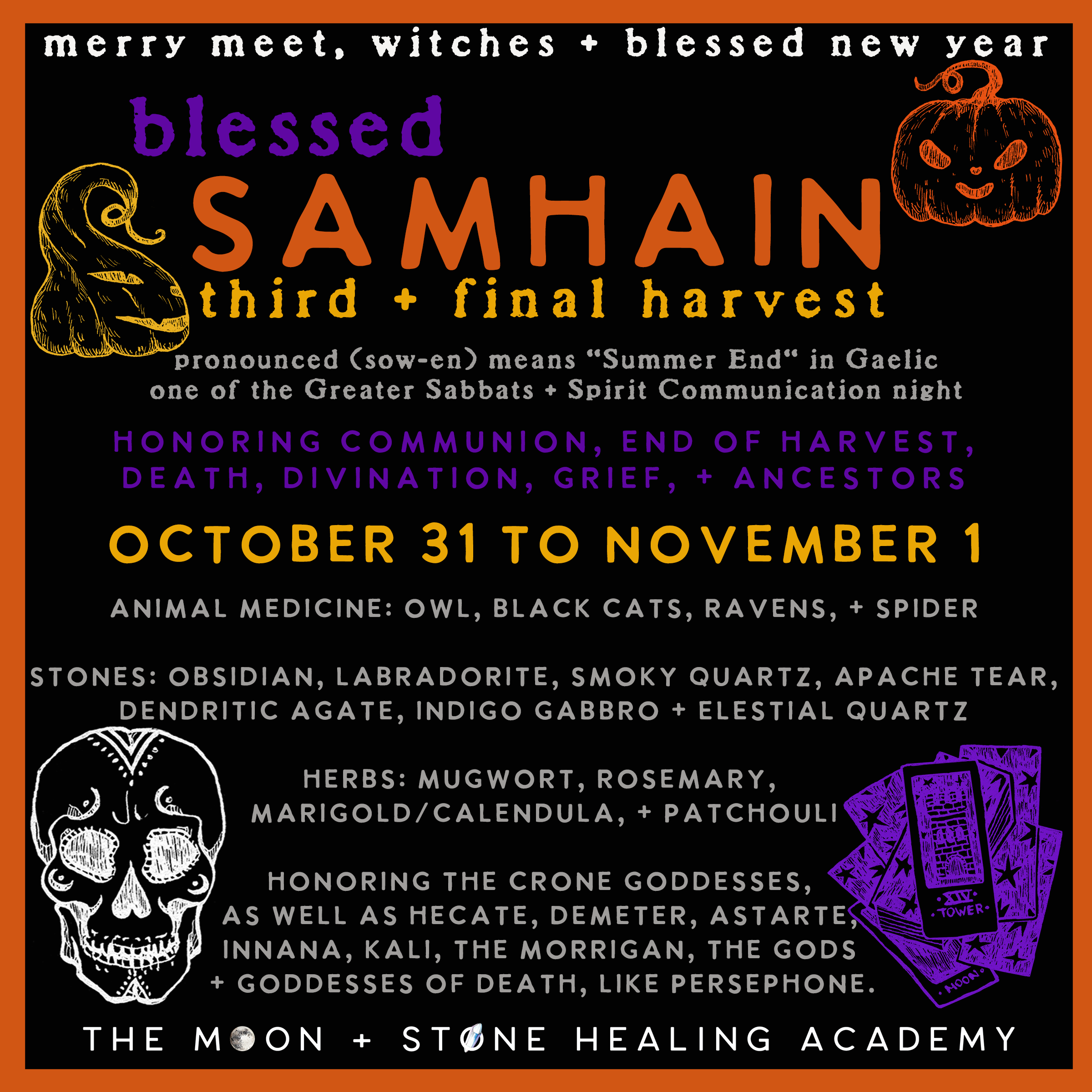

It is easy to create an ofrenda, or altar. Place photos of your relatives and ancestors in the space that feels sacred. I often use the top of my bookshelf or an undisturbed space. My mother uses her kitchen windowsill, which I always love too. You can put a candle, offerings of food, or herbs. Place a skull or skeleton (if you love the morbidity of representing the dead) and flowers. It can be as simple or as elaborate as you want. And you don't have to do this only for the ancestors you feel closest to, but also for those whose lessons were deep and difficult. Do it for your peace. If you have no ancestors you want to honor, do it for an artist you admire (Frida, anyone?), or a musician who has passed over. The days of the dead are considered October 31, November 1, and November 2nd. On October 31, All Hallows Eve, it is said the souls of the children who have died come back through the altars to the angelitos. According to tradition, the gates of heaven are opened at midnight on October 31, and the spirits of children can rejoin their families for 24 hours. The spirits of adults can do the same on November 2. November 1 is All Saints Day, when the ascended ones, saints, martyrs, and the angels are honored.

+ + + + +